Martians have been a fixture in literature, film, and popular culture for many years—but how did this idea come about? Surprisingly, it all started with a simple translation mistake. Here’s the story…

In 1863, Italian astronomer Pietro A. Secchi was observing Mars when he noticed lines on its surface that appeared to him as natural features of the terrain. He called them “canali,” an Italian term for channels or grooves.

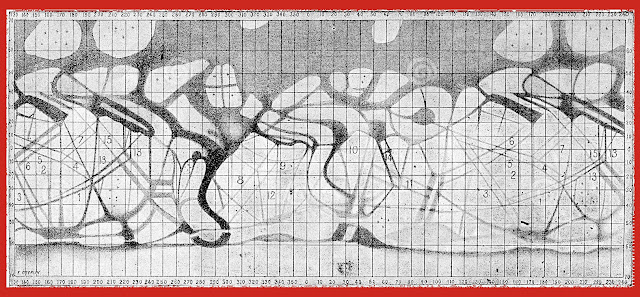

A few years later, in 1877, another Italian astronomer, Giovanni V. Schiaparelli, studied these lines with greater precision. Agreeing with Secchi that they were natural features, Schiaparelli conducted a detailed analysis and created a map, naming each line after biblical rivers (like Gihon or Pishon), mythological rivers (such as the Styx from Hades’ realm), or major rivers on Earth (like the Nile or Ganges).

He documented his findings in a scientific paper titled “Osservazioni astronomiche e fisiche sull’asse di rotazione e sulla topografia del pianeta Marte” (“Astronomical and Physical Observations on the Axis of Rotation and Topography of the Planet Mars”). The paper garnered significant attention, but its fame skyrocketed when it was translated into English—and that’s where the trouble began.

The translator made a critical error with the Italian word “canali.” The correct translation should have been “channels,” referring to natural formations. Instead, they chose “canals,” a word that implies man-made structures engineered by intelligent beings. Naturally, if the study suggested “artificial canals,” it implied that Mars was—or had once been—home to a sophisticated civilization capable of constructing massive waterways. These canals, it was reasoned, must have served a clear purpose: transporting water from the melting polar ice caps to the planet’s equatorial and desert regions.

This misunderstanding set the stage for a cultural phenomenon. Mars, Martians, and their canals captured the public’s imagination, especially when American astronomer Percival Lowell conducted new observations of the red planet between 1905 and 1909. Lowell published two wildly successful books that fueled the frenzy: Mars and Its Canals and Mars as the Abode of Life. The titles alone reveal how swiftly the notion of Martians spread across the globe.

Mars and its supposed inhabitants became deeply entrenched in popular culture, and nothing could dislodge them—not even more accurate observations. In 1909, Greek-French astronomer Eugène Michel Antoniadi studied Mars’ surface in far greater detail and found no trace of these “artificial canals.” Yet the idea persisted. Even NASA’s missions, starting with Mariner 4—which flew by Mars and sent back numerous photographs—failed to erase it. Neither did subsequent missions (including the rovers now traversing the planet’s surface or the probes that have orbited Mars for years), beaming thousands of images back to Earth daily.

Martians remain an integral part of our culture—and as we’ve seen, it all stems from a translation blunder. This raises a thought-provoking question: how many other “facts” we take for granted might also trace their origins to similar errors? It’s something worth pondering…

A few years later, in 1877, another Italian astronomer, Giovanni V. Schiaparelli, studied these lines with greater precision. Agreeing with Secchi that they were natural features, Schiaparelli conducted a detailed analysis and created a map, naming each line after biblical rivers (like Gihon or Pishon), mythological rivers (such as the Styx from Hades’ realm), or major rivers on Earth (like the Nile or Ganges).

He documented his findings in a scientific paper titled “Osservazioni astronomiche e fisiche sull’asse di rotazione e sulla topografia del pianeta Marte” (“Astronomical and Physical Observations on the Axis of Rotation and Topography of the Planet Mars”). The paper garnered significant attention, but its fame skyrocketed when it was translated into English—and that’s where the trouble began.

The translator made a critical error with the Italian word “canali.” The correct translation should have been “channels,” referring to natural formations. Instead, they chose “canals,” a word that implies man-made structures engineered by intelligent beings. Naturally, if the study suggested “artificial canals,” it implied that Mars was—or had once been—home to a sophisticated civilization capable of constructing massive waterways. These canals, it was reasoned, must have served a clear purpose: transporting water from the melting polar ice caps to the planet’s equatorial and desert regions.

This misunderstanding set the stage for a cultural phenomenon. Mars, Martians, and their canals captured the public’s imagination, especially when American astronomer Percival Lowell conducted new observations of the red planet between 1905 and 1909. Lowell published two wildly successful books that fueled the frenzy: Mars and Its Canals and Mars as the Abode of Life. The titles alone reveal how swiftly the notion of Martians spread across the globe.

Mars and its supposed inhabitants became deeply entrenched in popular culture, and nothing could dislodge them—not even more accurate observations. In 1909, Greek-French astronomer Eugène Michel Antoniadi studied Mars’ surface in far greater detail and found no trace of these “artificial canals.” Yet the idea persisted. Even NASA’s missions, starting with Mariner 4—which flew by Mars and sent back numerous photographs—failed to erase it. Neither did subsequent missions (including the rovers now traversing the planet’s surface or the probes that have orbited Mars for years), beaming thousands of images back to Earth daily.

Martians remain an integral part of our culture—and as we’ve seen, it all stems from a translation blunder. This raises a thought-provoking question: how many other “facts” we take for granted might also trace their origins to similar errors? It’s something worth pondering…

A journey through the history of the pharmaceutical industry and one of its great laboratories that had its origins in Alfred Nobel...

No comments:

Post a Comment